inclusion in the latest issue of SOILED: No. 6 Deathscrapers.

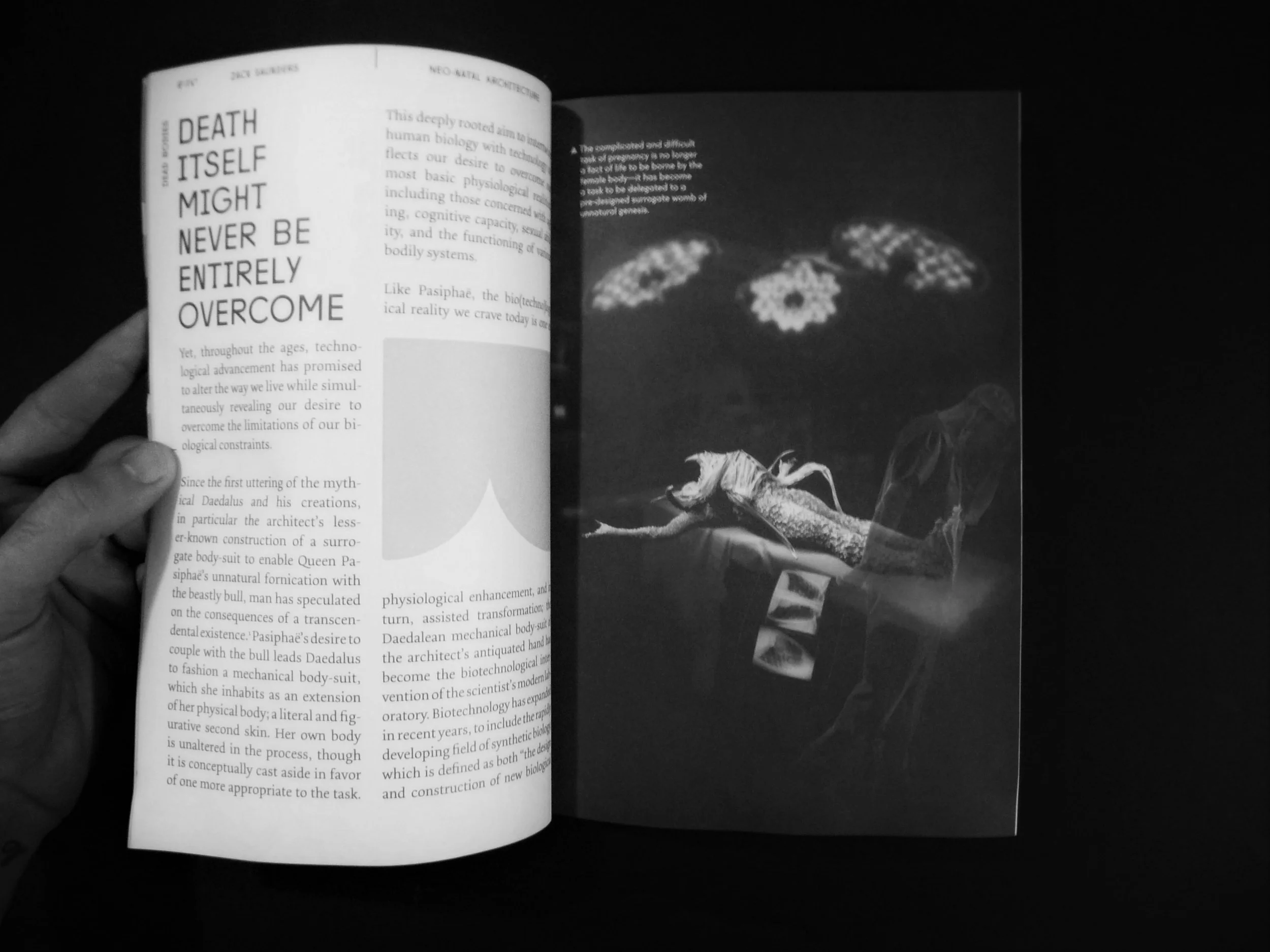

Death itself might never be entirely overcome. Yet, throughout the ages, technological advancement has promised to alter the way we live while simultaneously revealing our desire to utilize technology to overcome the limitations of our biological constraints.

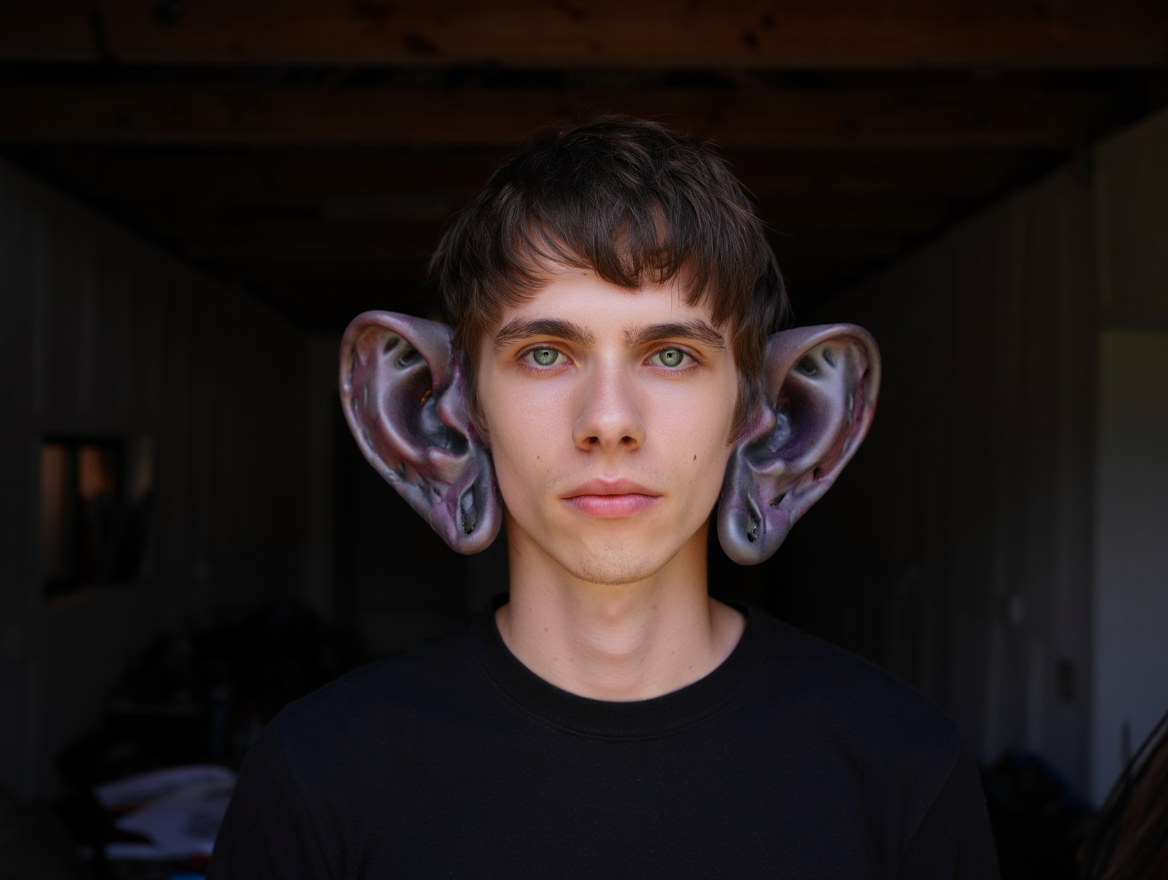

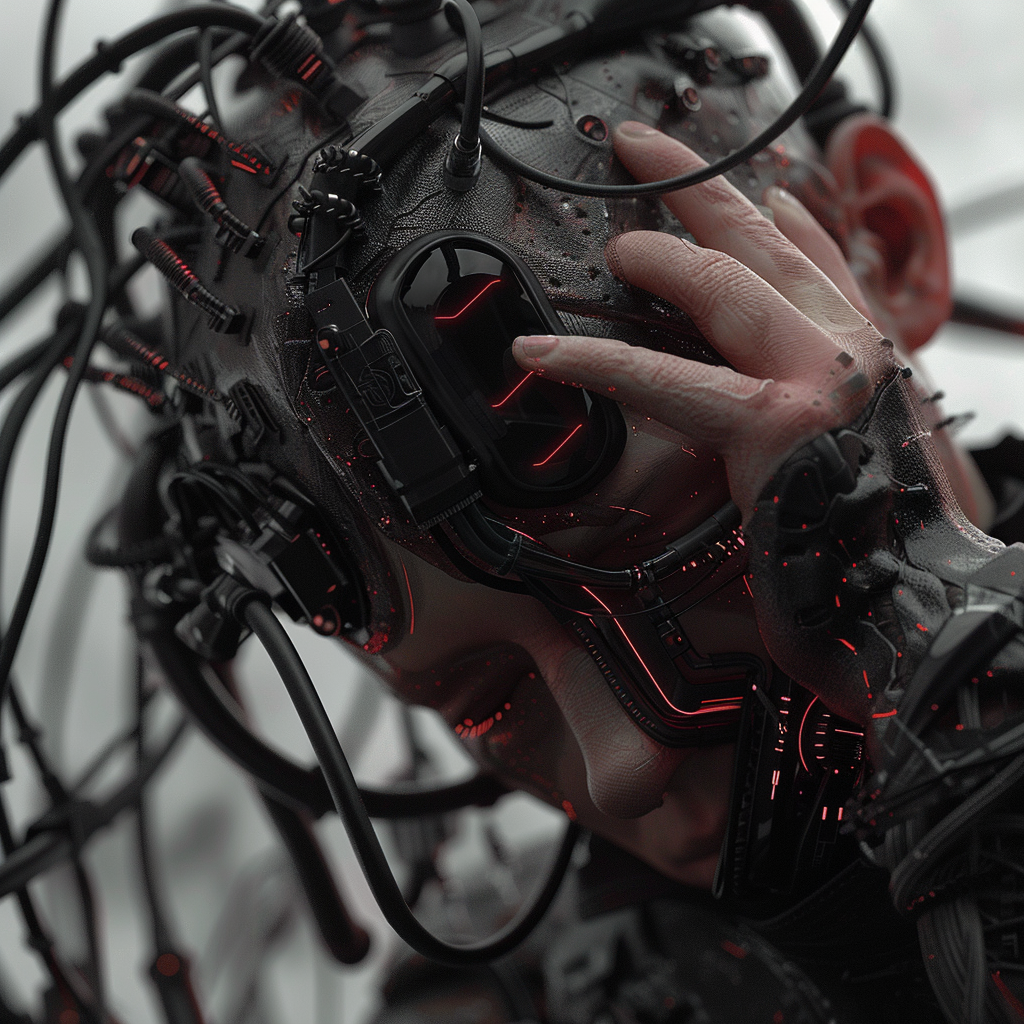

Since the first uttering of the mythical Daedalus and his creations, in particular the architect’s lesser-known construction of a surrogate body-suit to enable Queen Pasiphaë’s unnatural fornication with the beastly bull, man has speculated on the consequences of a transcendental existence (1). Pasiphaë’s desire to couple with the bull leads Daedalus to fashion a mechanical body-suit, which she inhabits as an extension of her physical body; a literal and figurative second skin. Her own body is unaltered in the process, though it is conceptually cast aside in favor of one more appropriate to the task. This deeply rooted aim to intertwine human biology with technology reflects our desire to overcome our most basic physiological realities, including those concerned with aging, cognitive capacity, sexual ability, and the functioning of various bodily systems.

Like Pasiphaë, the bio(techno)logical reality we crave today is one of physiological enhancement, and in turn, assisted transformation; the Daedalean mechanical body-suit of the architect's antiquated hand has become the biotechnological intervention of the scientist's modern laboratory. Biotechnology has expanded in recent years, to include the rapidly developing field of synthetic biology, which is defined as both “the design and construction of new biological parts, devices and systems” and “the re-design of existing, natural biological systems for useful purposes” (2). Today, we are reminded of such aspirations time and again: from Google's recent creation of a biotech research entity chiefly concerned with lifespan enhancement to Organovo's advances in 3D bioprinting (3).

Philosophers and futurists alike broadly coalesce to envision the emergence of a post-biological era, calling for the social acceptance of the marriage of technology and the human body. Transhumanism, for example, is primarily interested in “the opportunities for enhancing the human condition and the human organism opened up by the advancement of technology …. Transhumanists hope that by responsible use of science, technology, and other rational means we shall eventually manage to become post-human, beings with vastly greater capacities than present human beings have” (4). The desire to transcend the human condition, to become, in effect, “post-human,” is driving the technological agenda of today.

In light of such aims, supported by advances in bioprinting, genetic engineering, and tissue manufacturing in particular, it is probable that a transformation of the human body will not manifest solely in the form of disembodied technological artifacts or prosthetic devices, but rather in the form of highly sophisticated intrabody interventions which will fundamentally alter certain biological truths of the human body. The mechanical body-suit of the past is the genetically edited body of tomorrow.

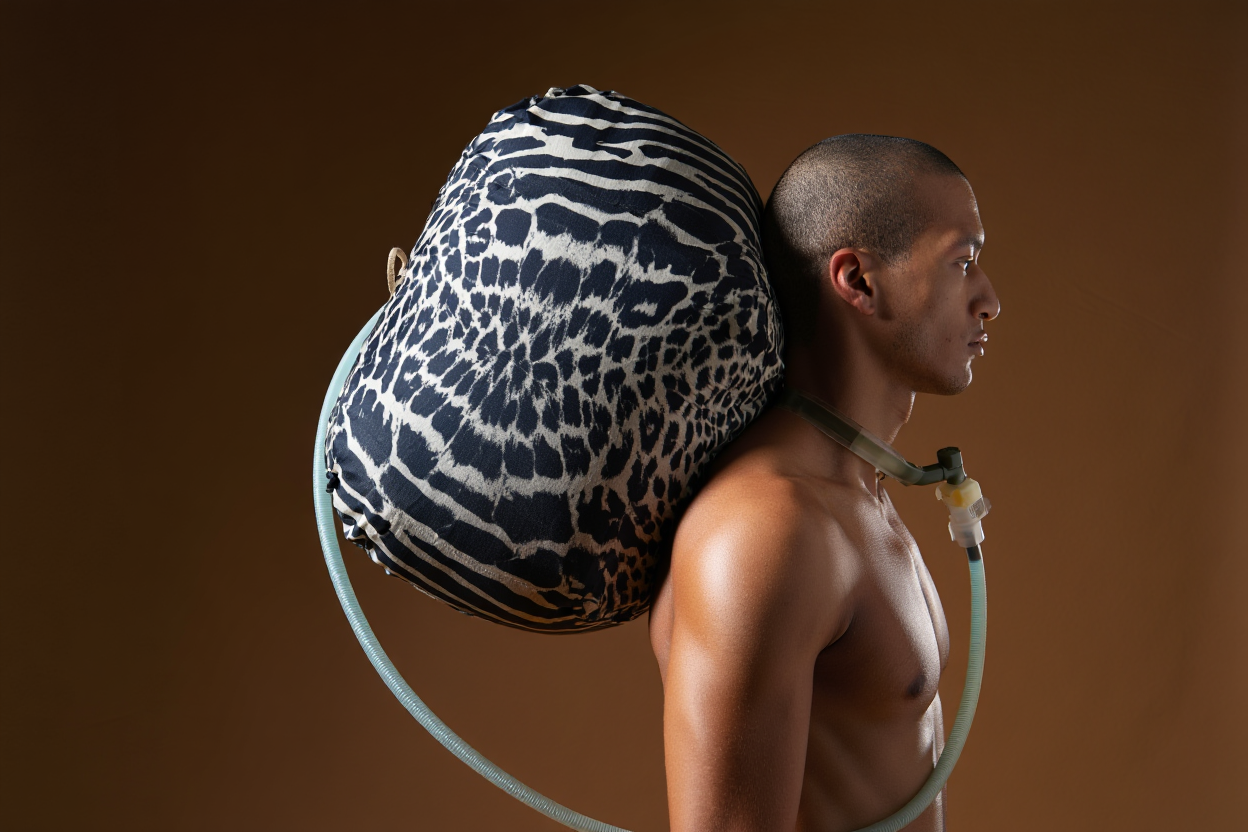

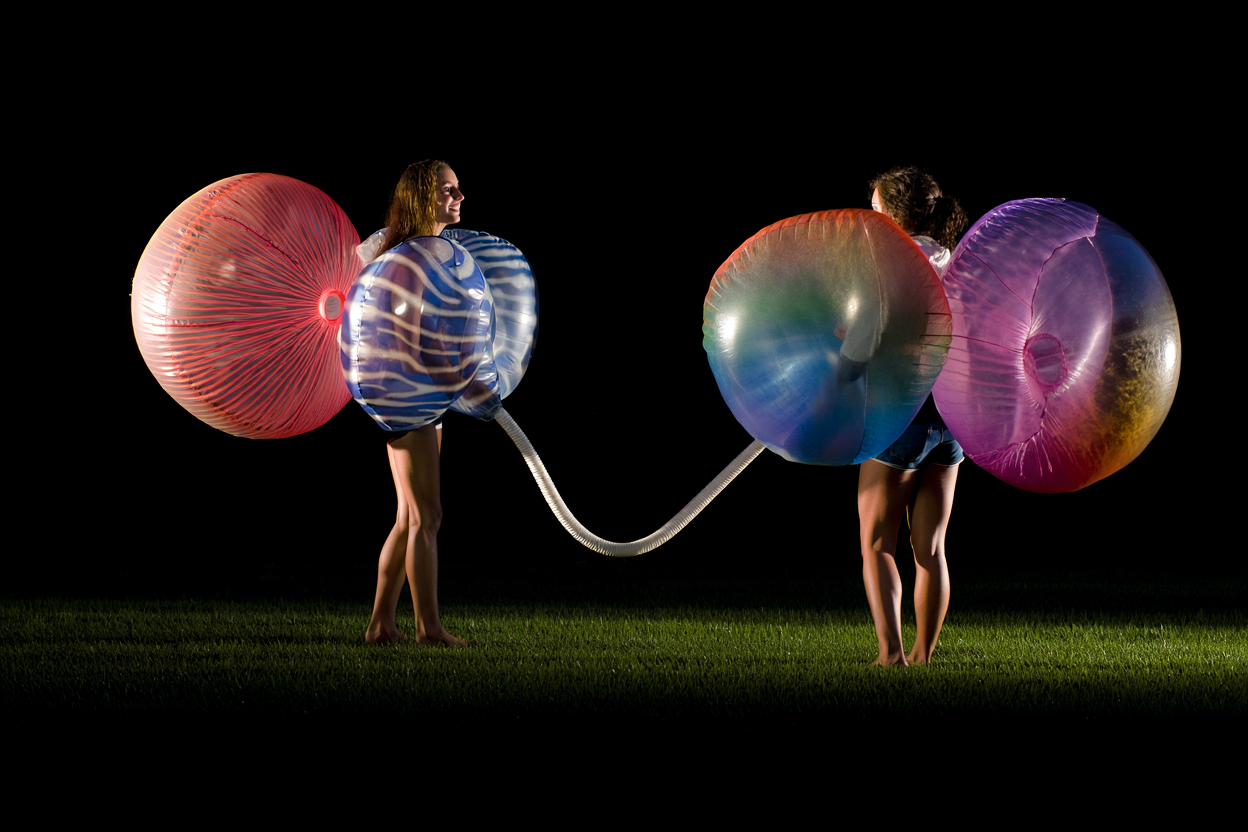

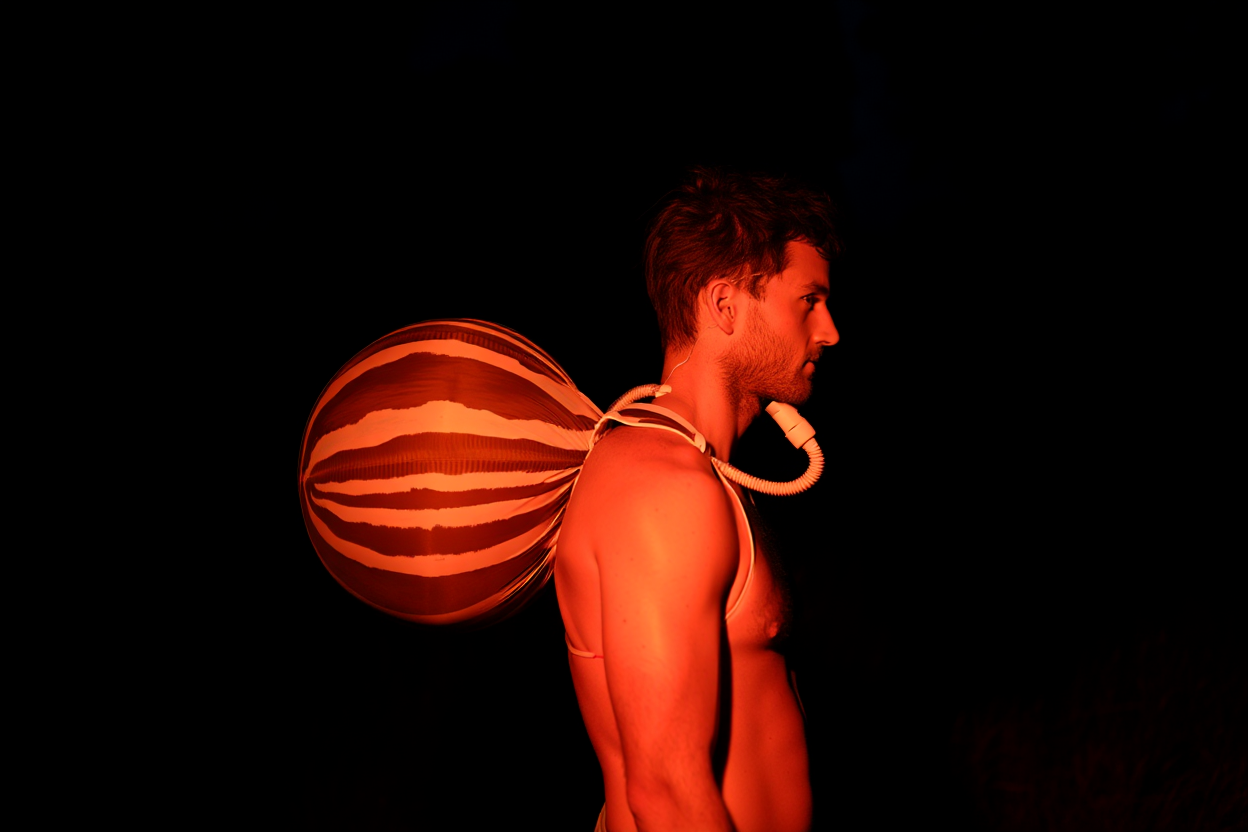

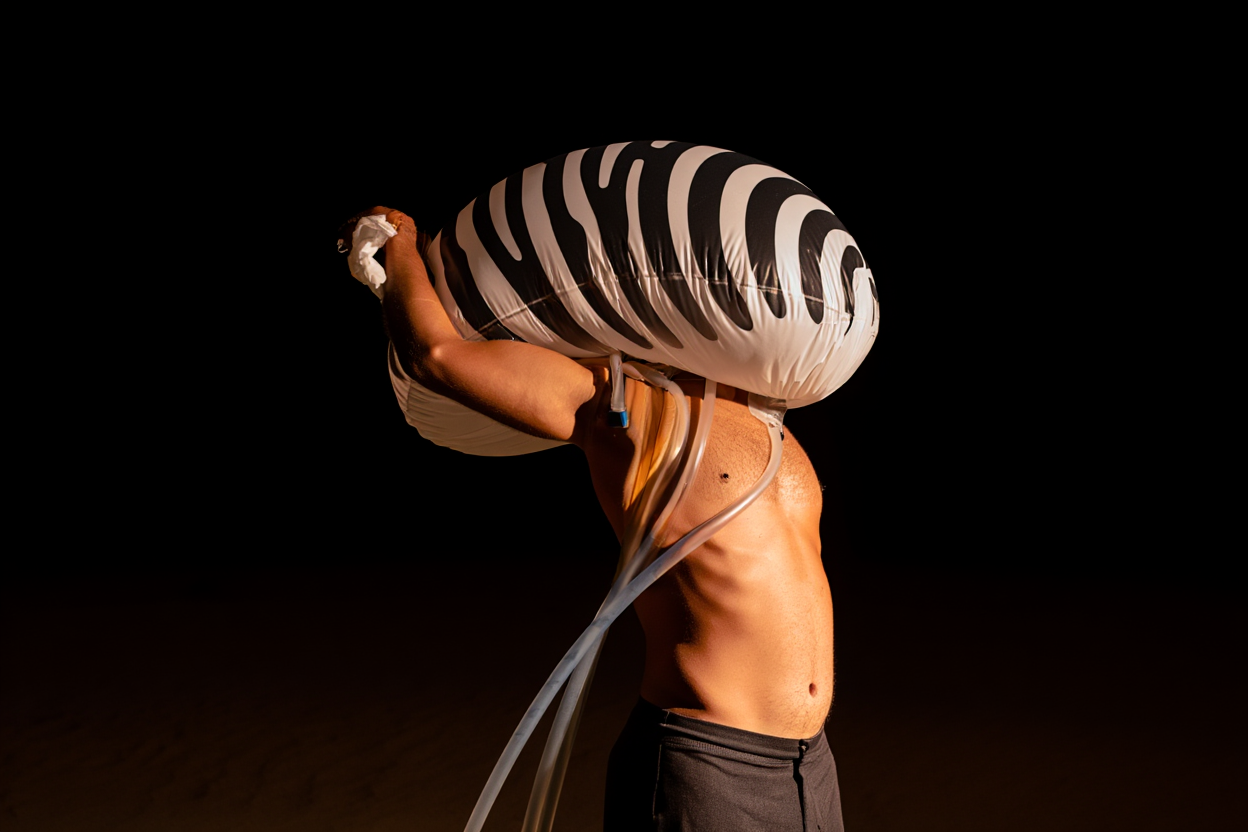

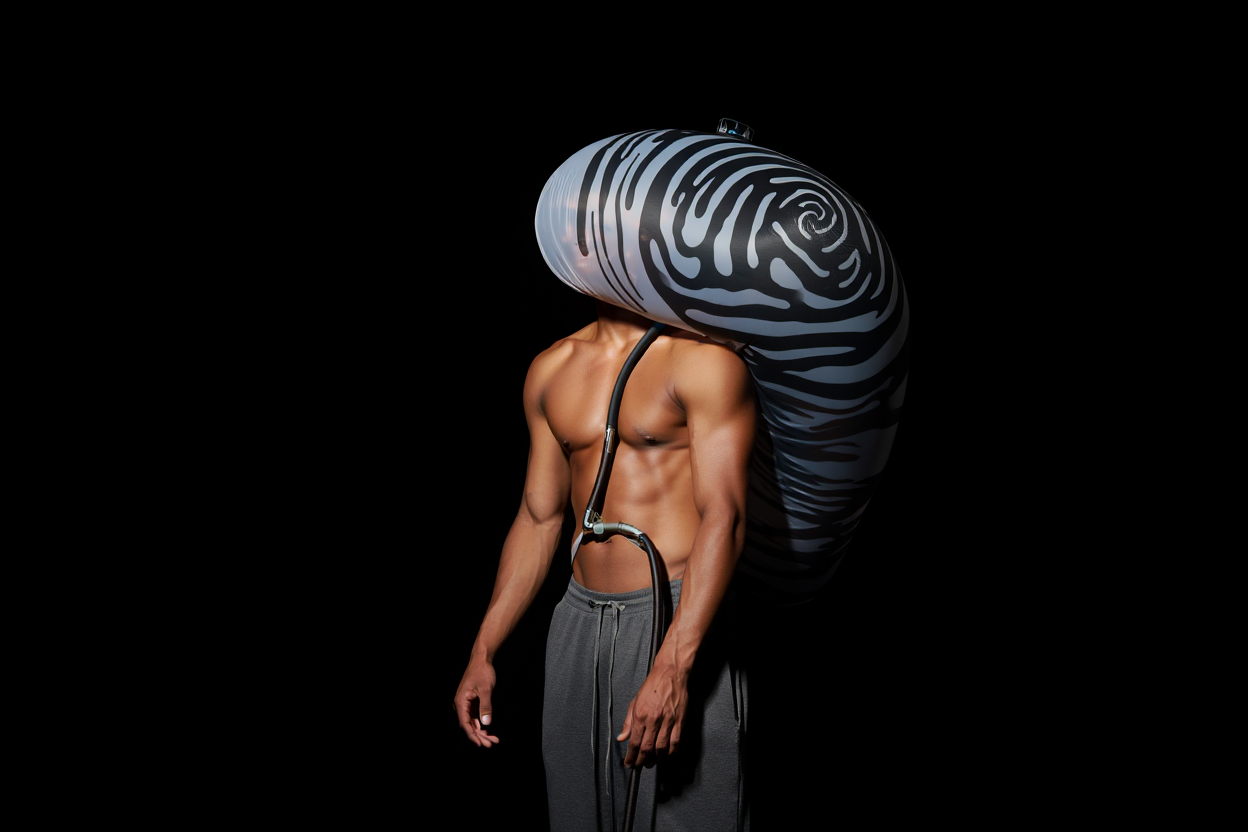

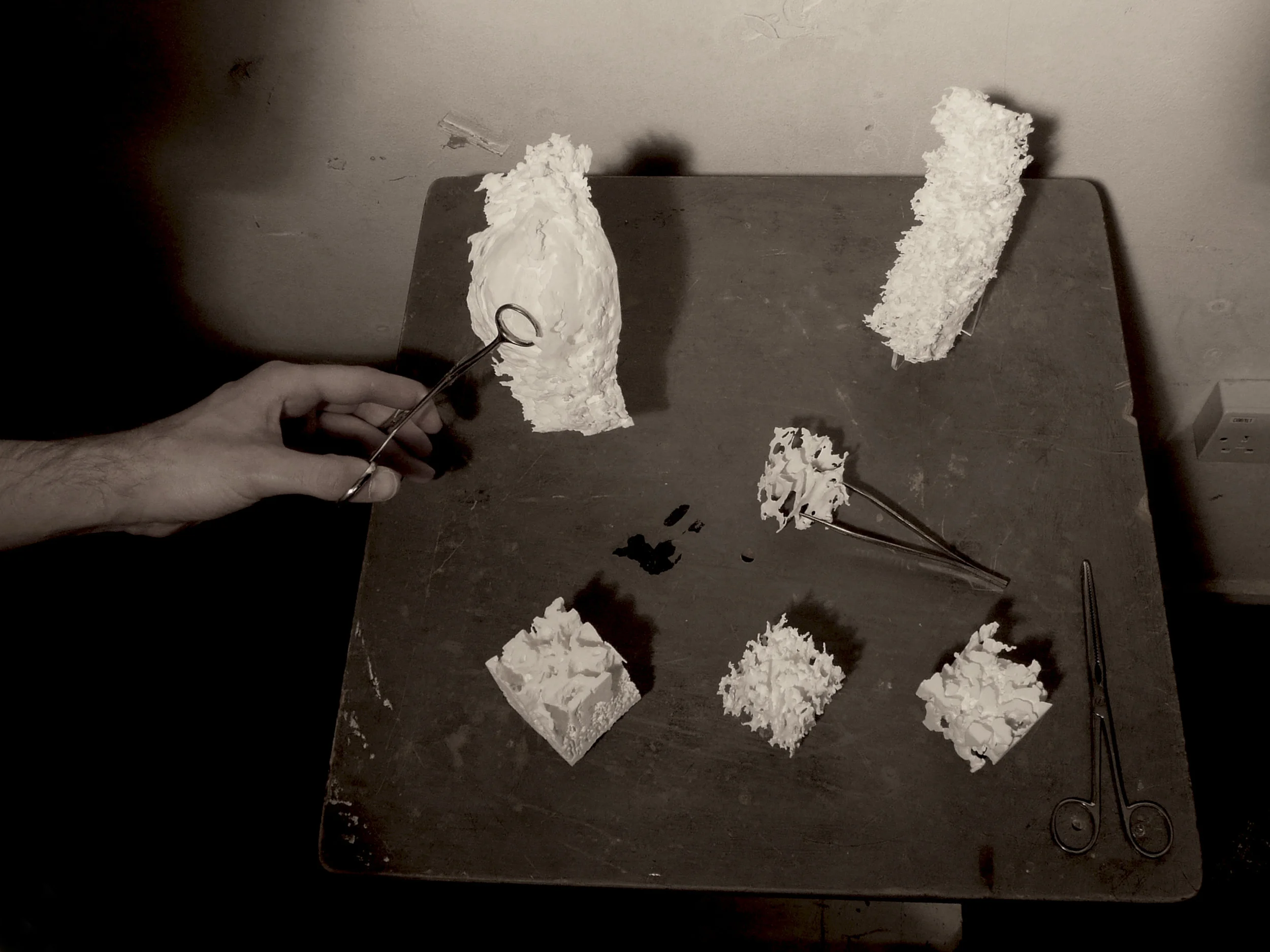

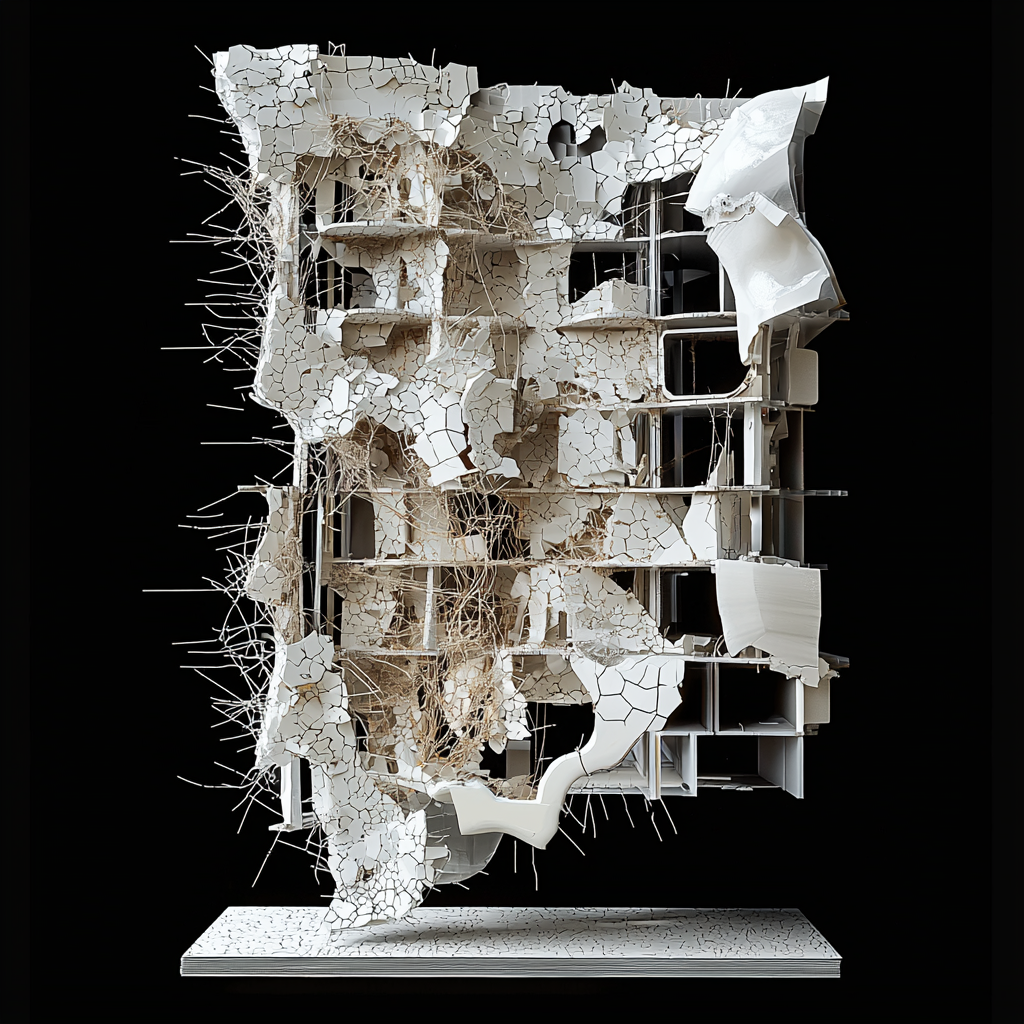

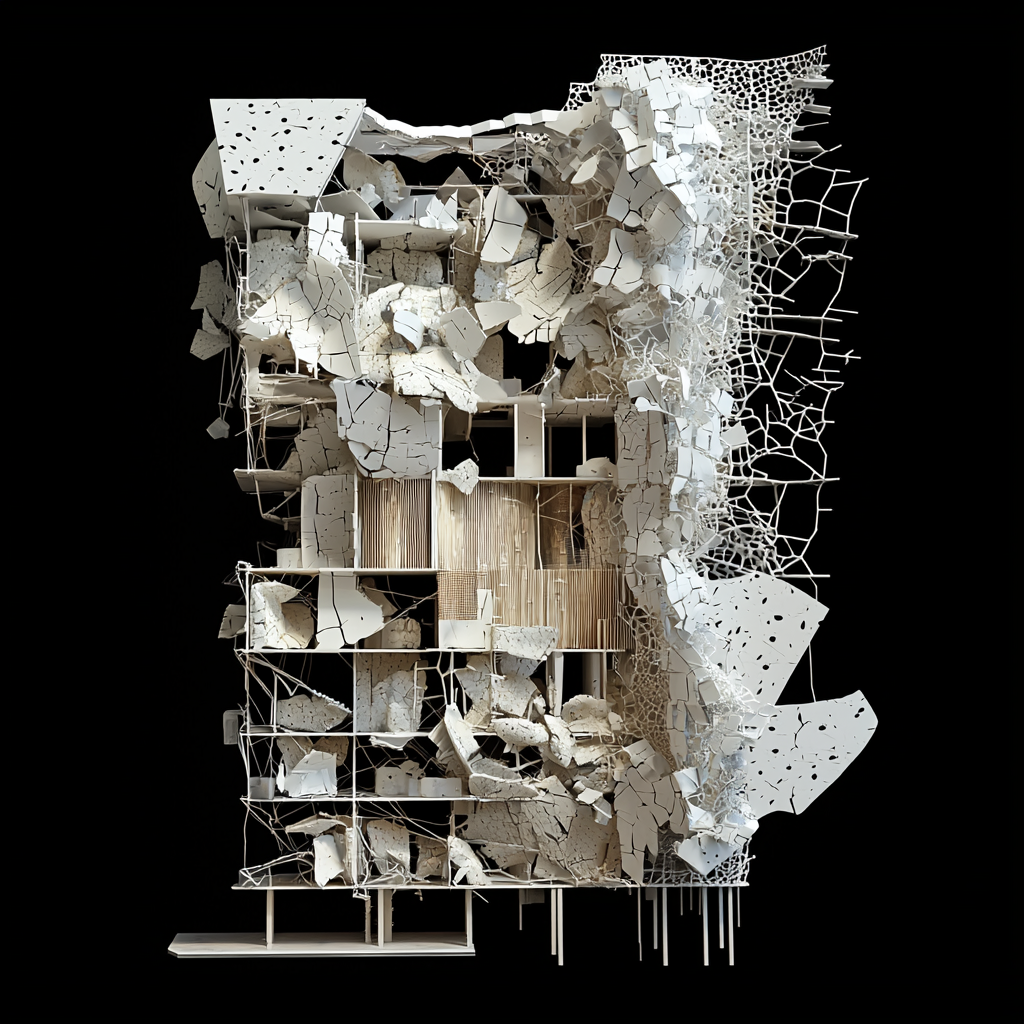

Operating as a kind of modern-day myth descriptive of a potential future scenario, Neonatal Architecture is rooted in a time where the human body itself, in the form of the inanimate corpse, is considered as a site for such an unnatural intervention. Human gestation, having previously been deemed an unnecessarily dangerous hardship for the human body to endure, and a particularly inconvenient one as well, has been completely supplanted by technological means – a hybrid between engineered tissues and fleshly human remains.

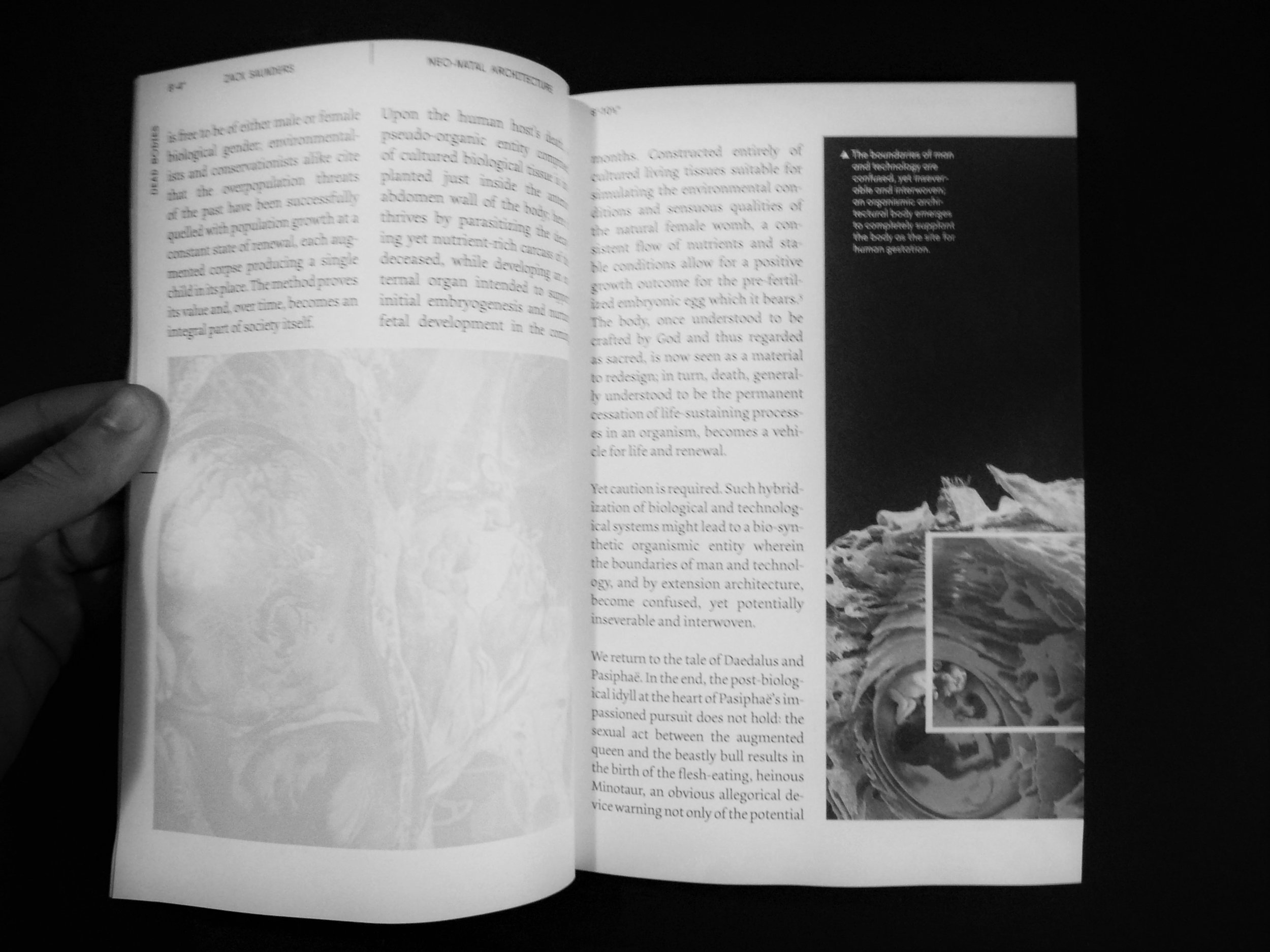

This new bodily extension acts solely as a surrogate womb, providing a safe and convenient substitute for traditional pregnancy and child birth. Leaders the world over endorse the method, noting the extreme drop in maternal and infant mortality rates; postgenderists rightfully declare the host body is free to be of either male or female biological gender; environmentalists and conservationists alike cite that the overpopulation threats of the past have been successfully quelled with population growth at a constant state of renewal, each augmented corpse producing a single child in its place. The method proves its value and, overtime, becomes an integral part of society itself.

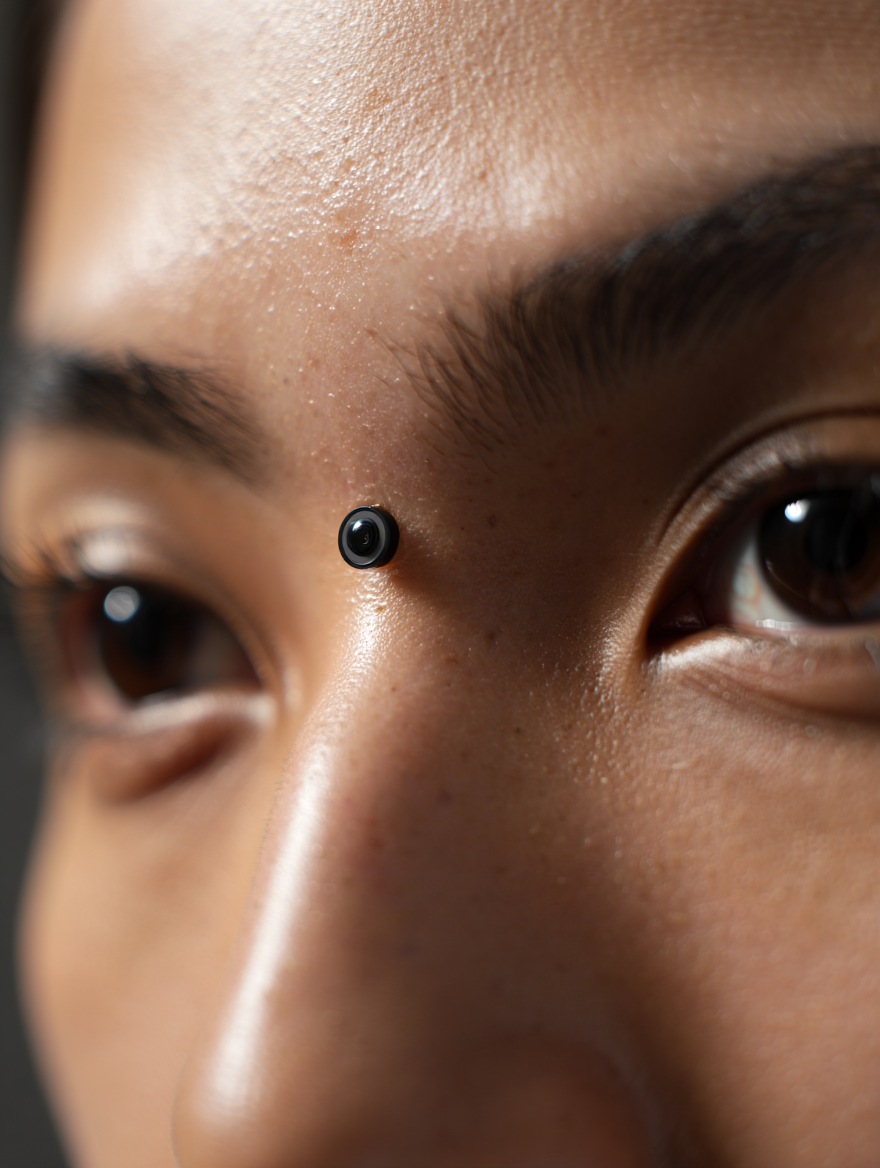

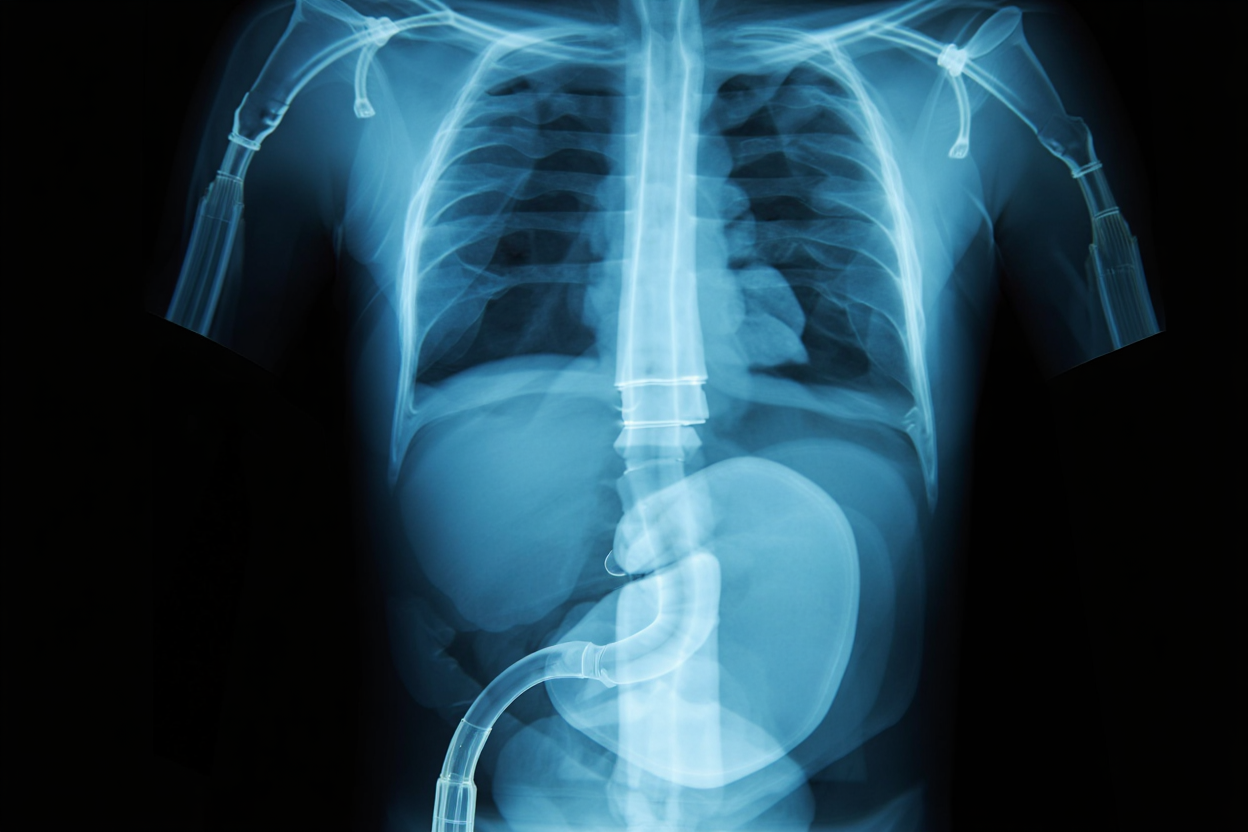

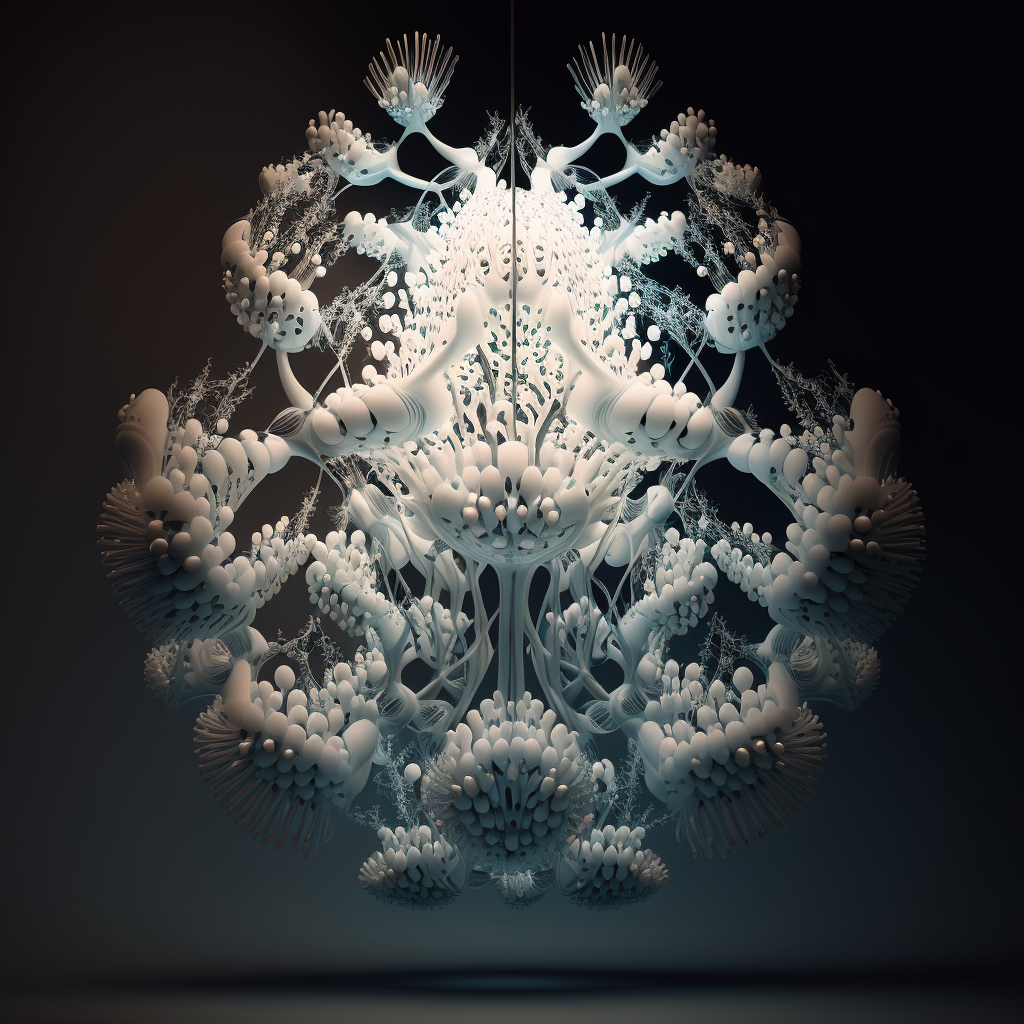

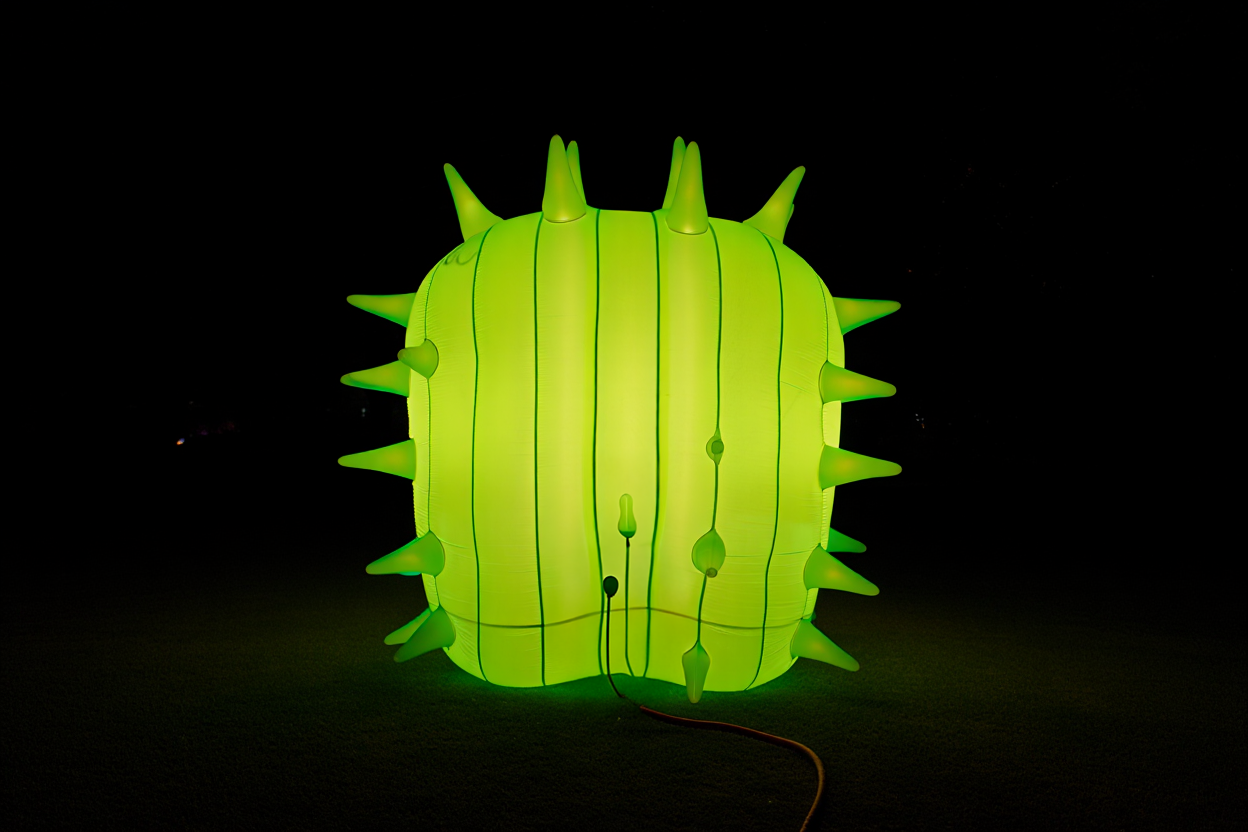

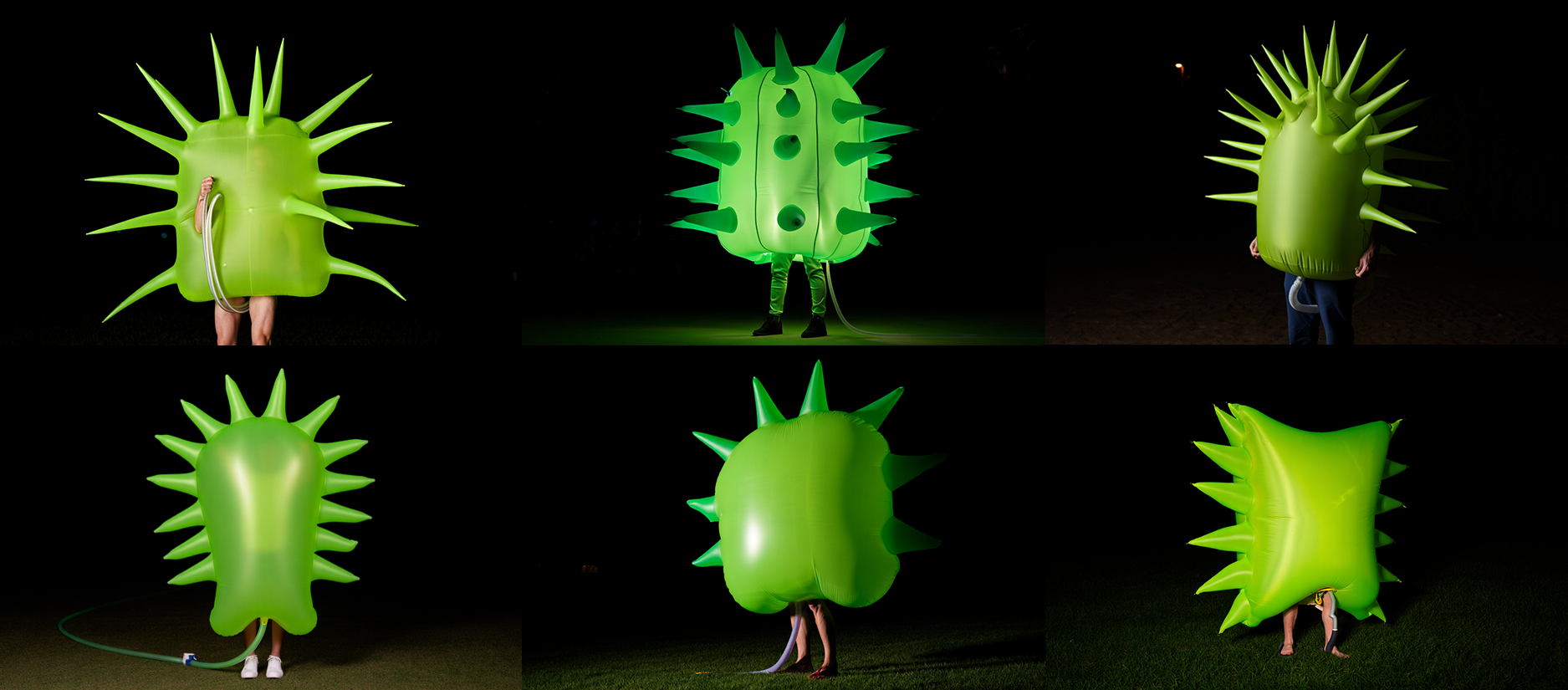

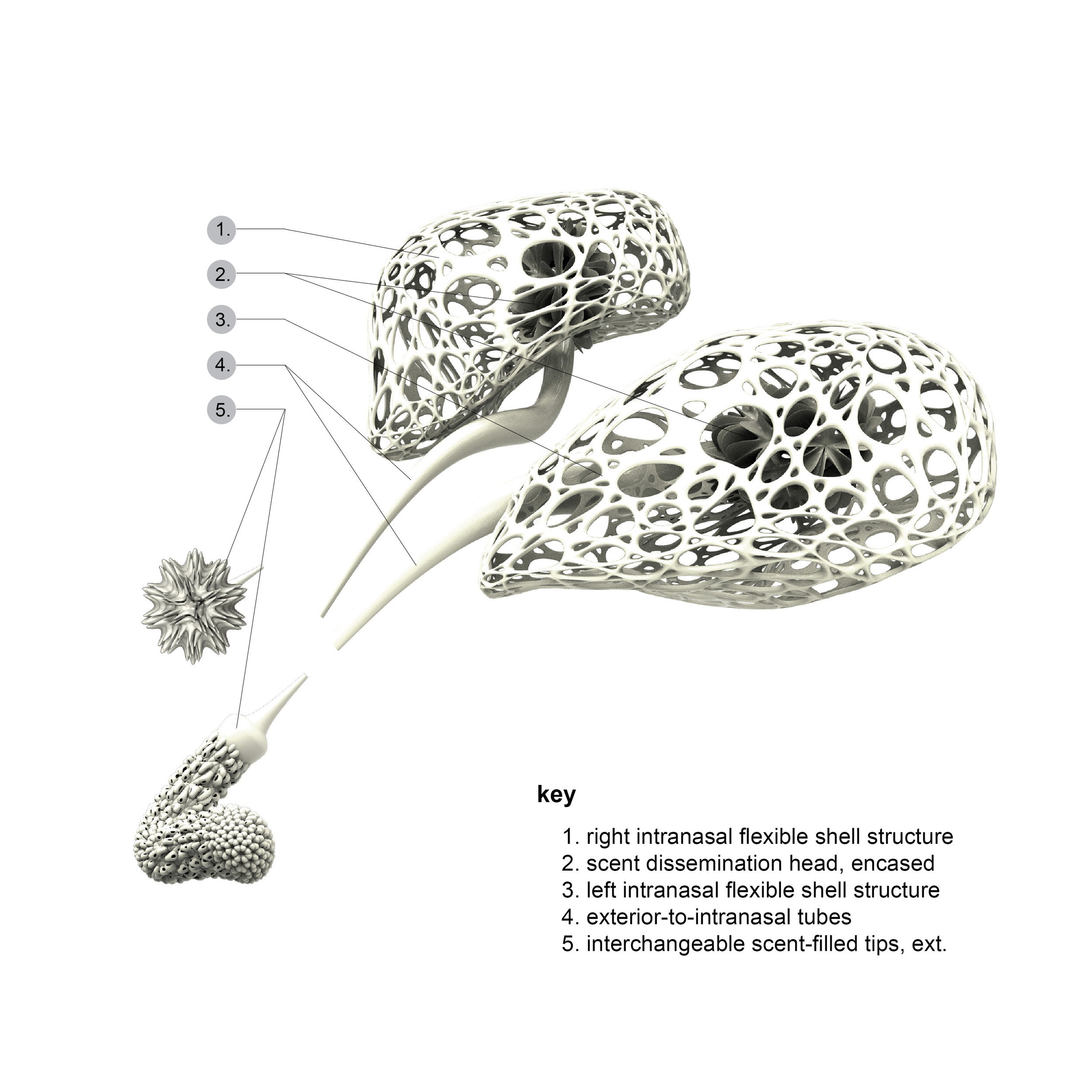

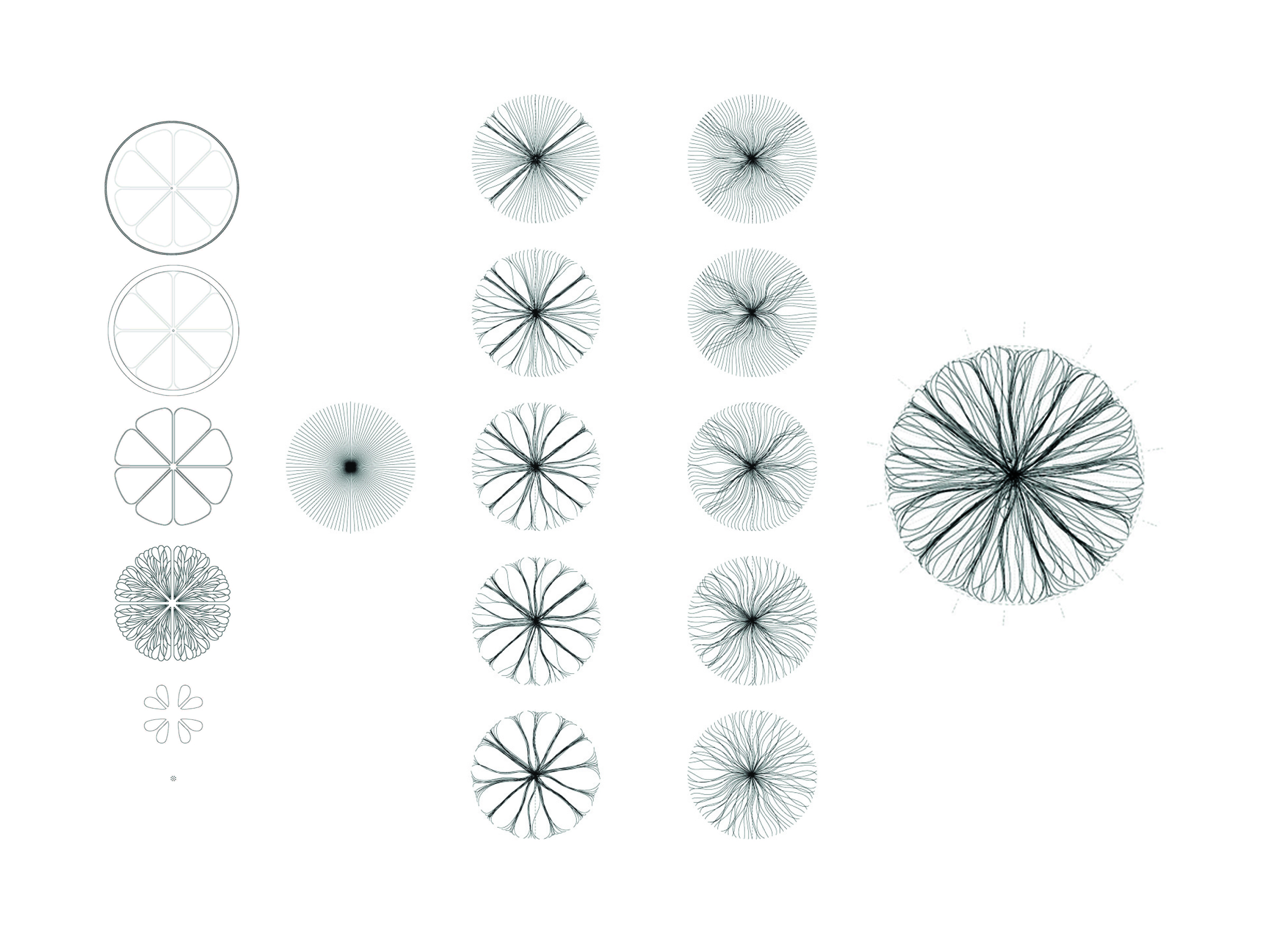

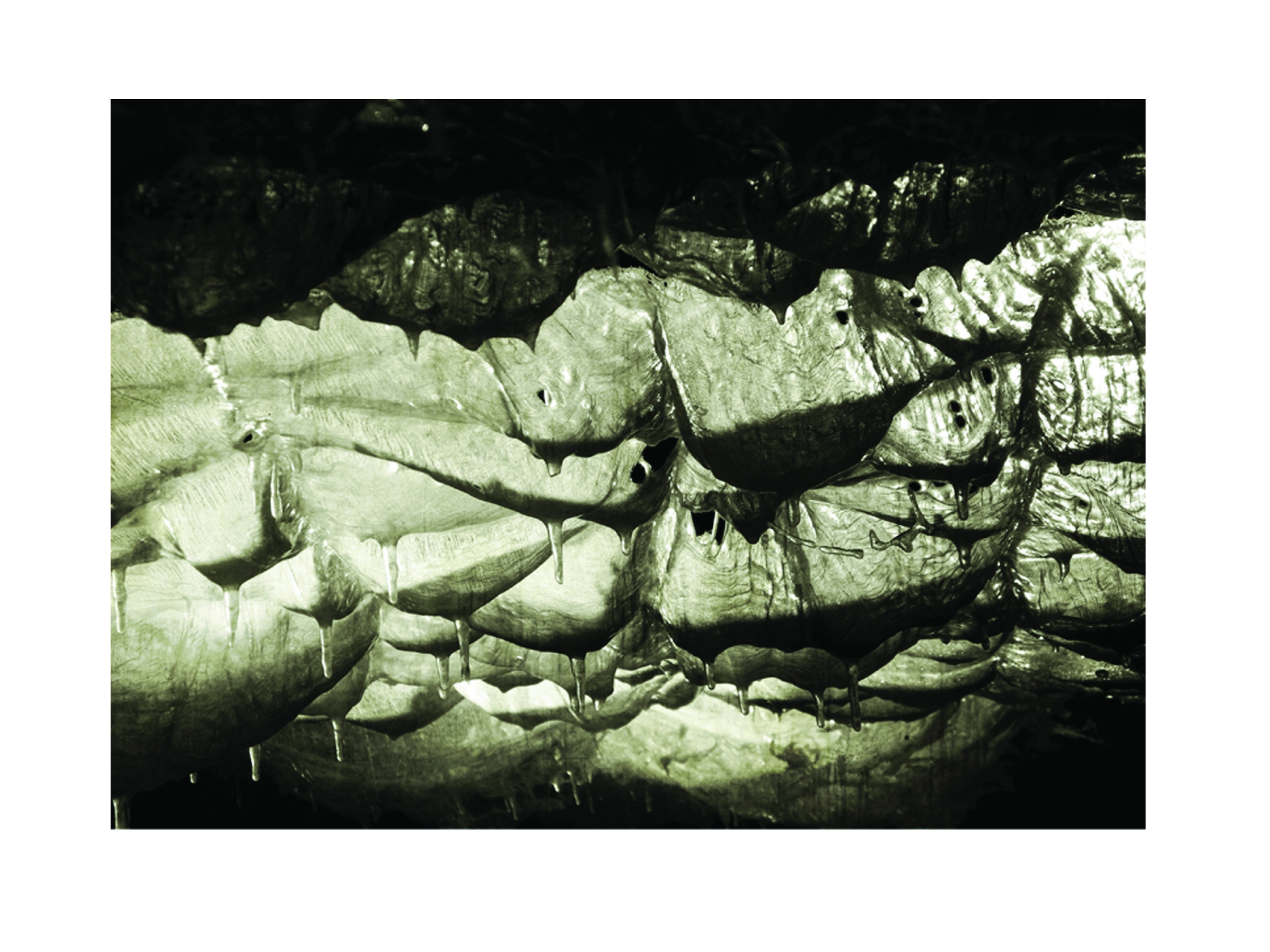

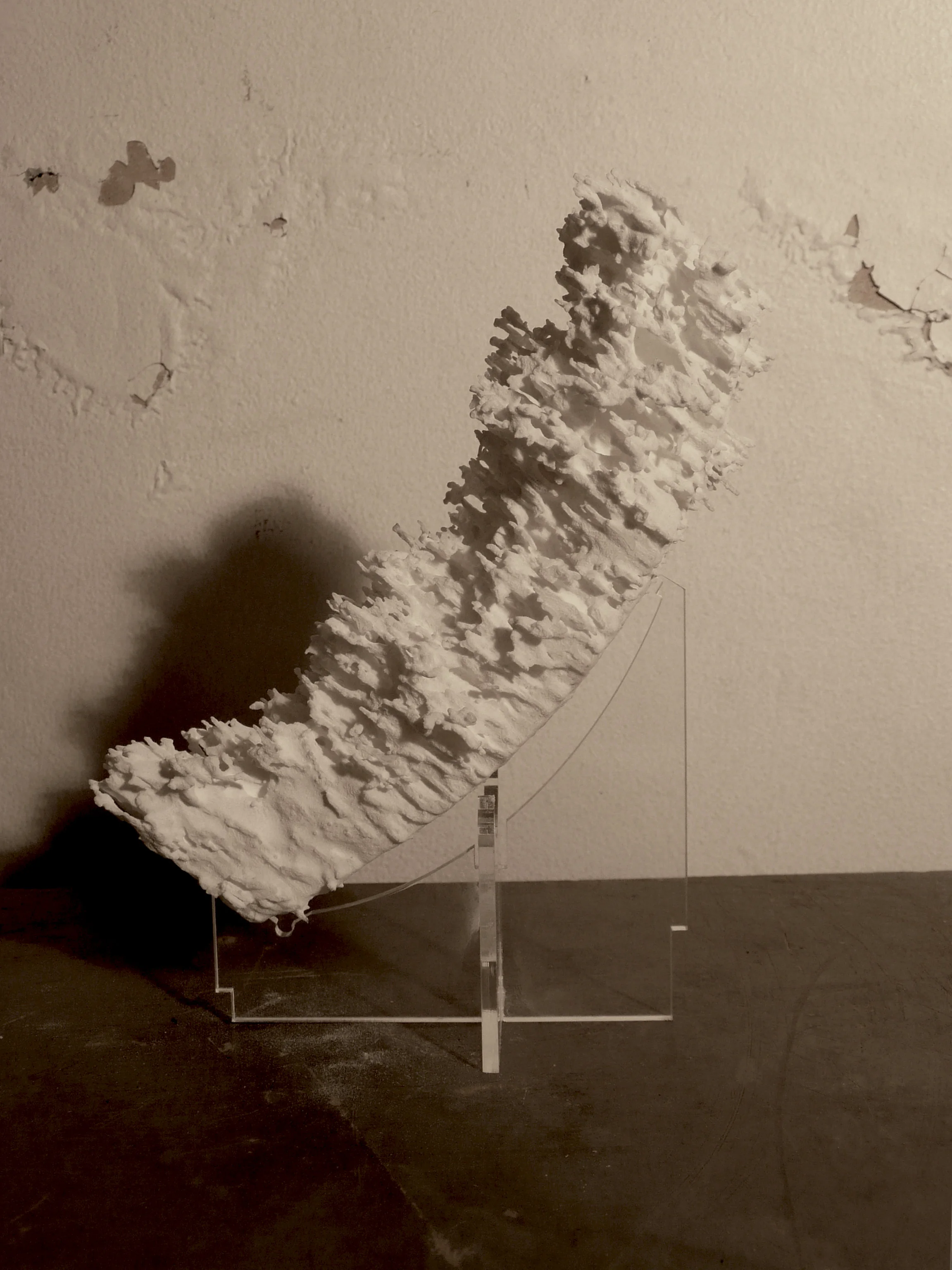

Upon the human host's death, a pseudo-organic entity comprised of cultured biological tissue is implanted just inside the anterior abdomen wall of the body; here it develops and thrives by parasitizing the decaying yet nutrient-rich carcass of the deceased. During initial development, the skin of the host body is breached by an external organ designed to support human embryogenesis and nurture fetal development in the coming months. Constructed entirely of cultured living tissues suitable for simulating the environmental conditions and sensuous qualities of the natural female womb, a consistent flow of nutrients and stable conditions allow for a positive growth outcome for the pre-fertilized embryonic egg which it bears (5).

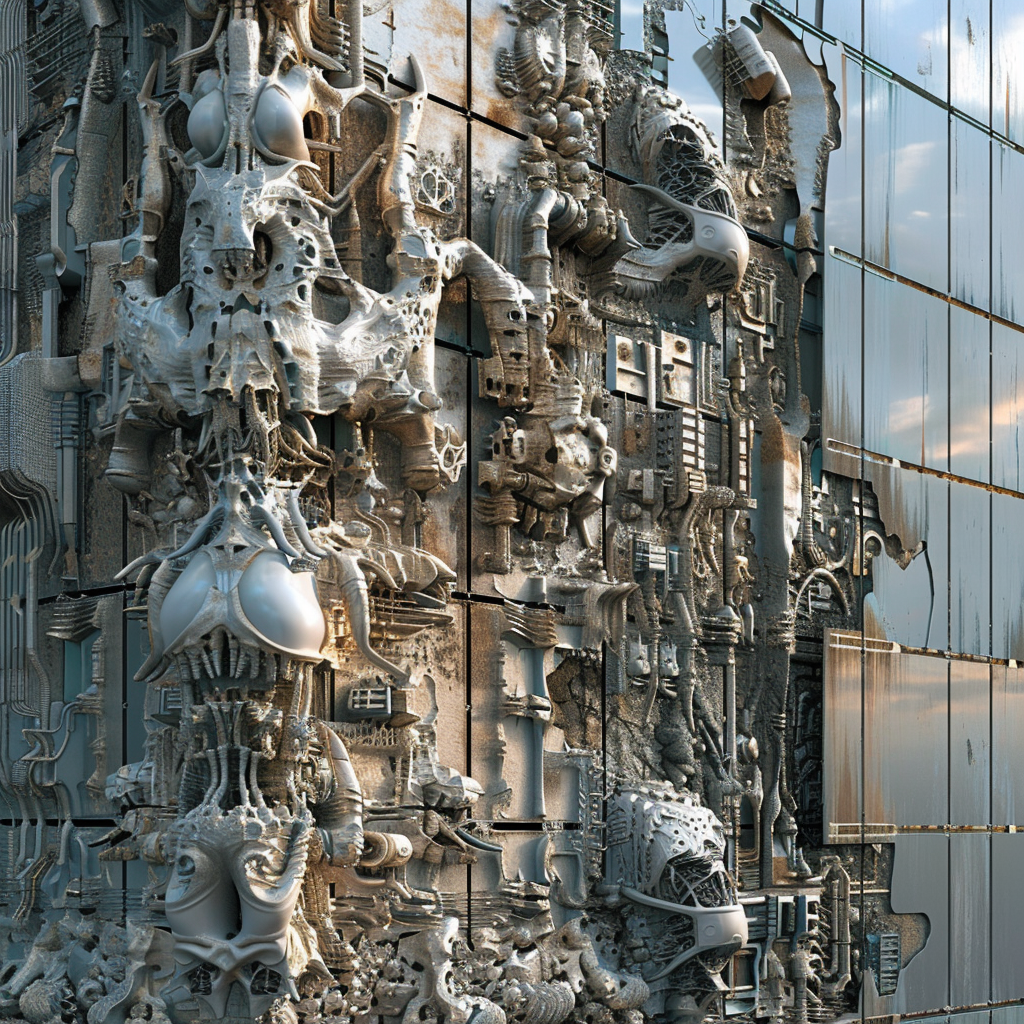

The human body, once understood to be crafted by God and thus regarded as sacred, is now seen as a material to be modified; at the same time, death, generally understood to be the permanent cessation of life-sustaining processes in an organism, becomes a vehicle for life and renewal. However, while such technological progress stands to alter the way we live for the better, the hybridization of natural and quasi-natural systems might lead to a bio-synthetic organismic entity wherein the boundaries of man and technology, and by extension architecture, become confused, yet potentially inseverable and interwoven.

We return to the tale of Daedalus and Pasiphaë. For Pasiphaë, the act of selecting a specific, appropriately designed body was driven by her primary desire to couple with the bull, a yearning which resulted from her being cursed by the gods to harbor such passion in the first place. All else, aside from her lustful ambition, faded from the queen's view. Ironically, however, the post-biological idyll at the heart of Pasiphaë’s impassioned pursuit does not hold in the end: the sexual act between the augmented queen and the beastly bull results in the birth of the flesh-eating, heinous Minotaur, an obvious allegorical device warning not only of the potential danger inherent in pursuing unnatural desire, but also alluding to the uncharted consequences resulting from biotechnological enhancement.

In the time of Daedalus, life on this earth was considered to be a short journey which, upon one's death, led to the infinite afterlife. Today, on the other hand, we harbor no such notions. Life on this earth is understood by modern secular man to be all there is. Death is considered to be the end. In light of this fundamental shift in perspective, it seems only natural that we should want to enhance our lives as much as possible. However, as we enter a future where the desire to transcend our natural limitations is actually enabled by technological means, we must ask if the Daedalean myth of the past, laced with poetical reflections on the human condition alongside fantastical yet carefully considered explorations of its boundaries, has been forgotten, cast aside in favor of a lustful embrace of such a future, without question?

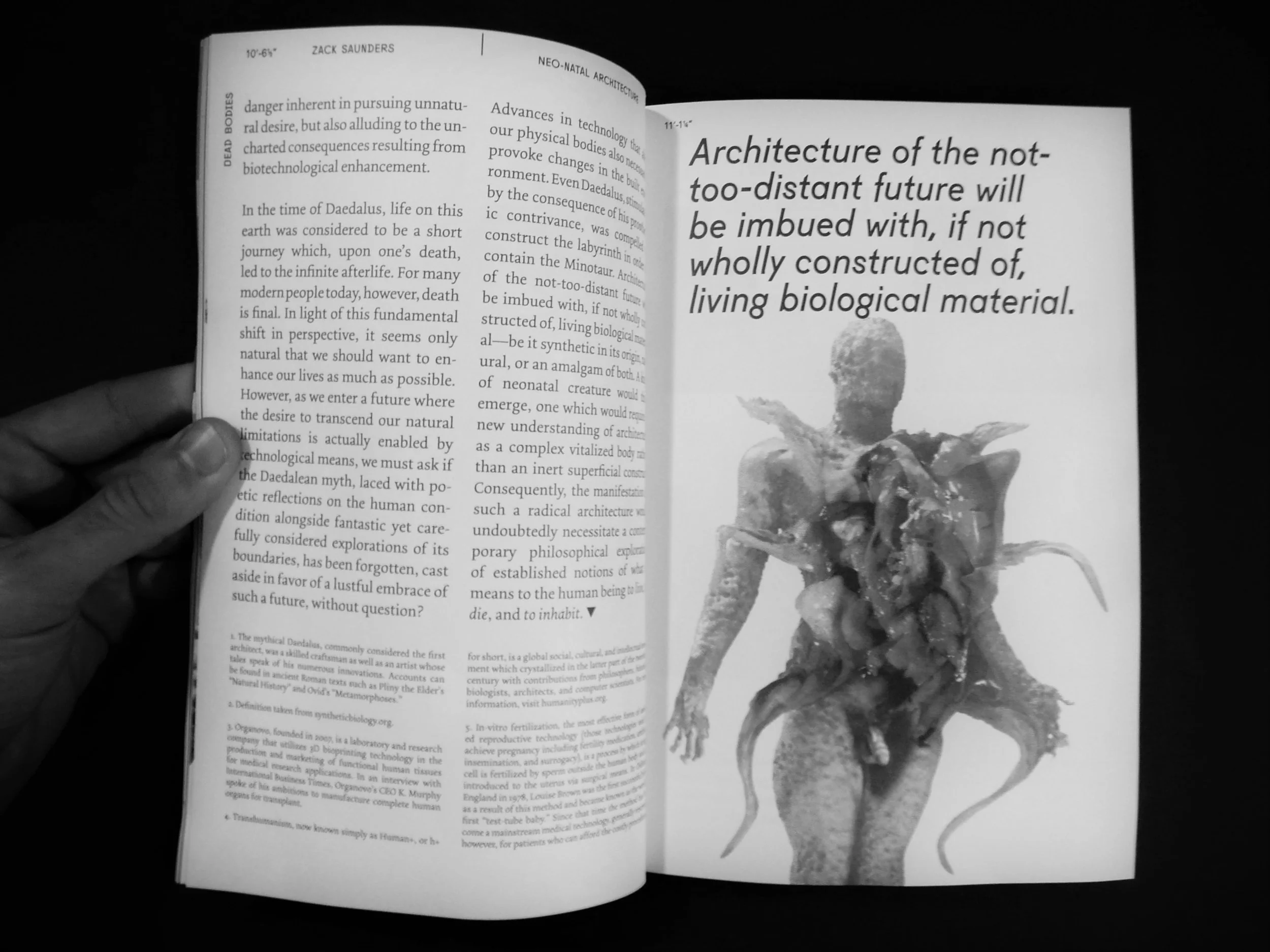

Advances in technology that alter our physical bodies will inevitably inspire correlative changes in the built environment. Even Daedalus, stimulated by the consequence of his prosthetic contrivance, was compelled to construct the Labyrinth in order to confuse and contain the Minotaur. Architecture of the not-too-distant future will quite possibly be imbued with, if not wholly constructed of, living biological material – be it synthetic in its origin, natural, or an amalgam of both. A kind of neonatal creature would thus emerge, one which would call for a new understanding of architecture as a complex vitalized body rather than an inert superficial construct. The human body, as an altered bio-technological entity, would also require a reexamination, not only of its own newfound condition, but also of its relationship to its contemporaneous environment.

The Labyrinth, the fabled mediator between the natural and the unnatural, must be expanded in the future from its storied role as a structure of abyssal seclusion to a similarly convoluted yet increasingly intimate system of newfound interactions between the post-human and architecture, one with the potential to form novel ecological relationships; the specific outcomes of which can only be speculated upon. Perhaps the mere conceptualization of such a biotechnological future necessitates an appropriate philosophical exploration of established notions of what it means to the human being to live, to die, and to inhabit.

NOTES:

1.) The mythical Daedalus, commonly considered the first architect, was a skilled craftsman as well as an artist whose tales speak of his numerous innovations; of particular interest here are his efforts to enhance the human body via technological prosthesis and extension. Accounts can be found in ancient Roman texts such as Pliny the Elder's “Natural History” and Ovid's “Metamorphoses.”

2.) Definition taken from syntheticbiology.org.

3.) Organovo, founded in 2007, is a laboratory and research company that utilizes 3D bioprinting technology in the production and marketing of functional human tissues for medical research applications. In an interview with International Business Times, Organovo’s CEO K. Murphy spoke of his ambitions to manufacture complete human organs for transplant. The company made international headlines in 2015 when it entered an agreement with skincare company L'Oreal to provide 3D printed human skin tissue for product testing purposes.

4.) Transhumanism, now known simply as Human+, or h+ for short, is a global social, cultural, and intellectual movement which crystallized in the latter part of the twentieth century with contributions from philosophers, futurists, biologists, architects, and computer scientists. For more information, visit humanityplus.org.

5.) In-vitro fertilization, the most effective form of assisted reproductive technology (those technologies used to achieve pregnancy including fertility medication, artificial insemination, and surrogacy), is a process by which an egg cell is fertilized by sperm outside the human body and reintroduced to the uterus via surgical means. In Oldham, England in 1978, Louise Brown was the first successful birth as a result of this method and became known as the world’s first “test-tube baby”; in-vitro literally translating as “in glass.” Since that time the method has become a mainstream medical technology, generally reserved, however, for patients who can afford the costly procedures.

. . .

SOILED Issue No. 6 Deathscrapers. Cartogram, 2016. Print. p 1-12. Participation in accompanying group exhibition, 2016. Location: 1530 West Superior Street, Chicago IL 60642. Exhibition photographs courtesy of SOILED.

![ARCH [or] studio](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54581704e4b076d6c3dd5550/c11f2faa-8dad-4219-971e-aef0d7ad9010/AoS+NEW+LOGO+01.png?format=1000w)